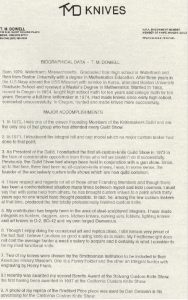

There are hundreds of published articles about Ted and/or TMD Knives. The list is both comprehensive and chronological, and can be found the ‘Archives & Reference’ section of this site; along with a number of in-depth articles written on TMD. The first of these ‘articles’, a biography authored by the maker, is representative of the man who ‘could say so much, with so few words’, as attributed to him on more than occasion by industry writers and pundits.

There are hundreds of published articles about Ted and/or TMD Knives. The list is both comprehensive and chronological, and can be found the ‘Archives & Reference’ section of this site; along with a number of in-depth articles written on TMD. The first of these ‘articles’, a biography authored by the maker, is representative of the man who ‘could say so much, with so few words’, as attributed to him on more than occasion by industry writers and pundits.

[Hint: you can expand any photos or linked words by simply clicking on them]

Ted was born and raised in Watertown, MA, in 1929. The family house was a two-story unit, with a ‘workshop’ in the basement garage. Ted’s father was a handyman, and worked in construction, auto mechanics, and a variety of trades of the time. Ted was attracted to the shop area at a very young age, where he found a wood lathe, a drill press, a small band saw, a small grinder/belt sander, and a wide selection of tools and vices, for working on automobiles.

During WWII, as a child, Ted’s father taught him the basics of automobile mechanics. The Dowell’s became well known throughout the neighborhood for being able to keep ‘family and friends’ automobiles up and running at a time when parts were particularly scarce due to the war efforts. Because Dowell’s had figured out how to create makeshift parts from various scrap metals, they were able to work around some of the parts shortage issues by salvage and modification, or by creating them from scratch. These experiences served as valuable training for Ted’s development and enhancement of his mechanical, engineering, and artistic skills – all of which eventually proved very handy when it came to making knives.

During WWII, as a child, Ted’s father taught him the basics of automobile mechanics. The Dowell’s became well known throughout the neighborhood for being able to keep ‘family and friends’ automobiles up and running at a time when parts were particularly scarce due to the war efforts. Because Dowell’s had figured out how to create makeshift parts from various scrap metals, they were able to work around some of the parts shortage issues by salvage and modification, or by creating them from scratch. These experiences served as valuable training for Ted’s development and enhancement of his mechanical, engineering, and artistic skills – all of which eventually proved very handy when it came to making knives.

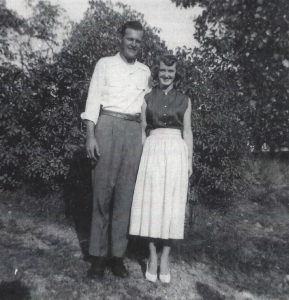

Dowell met his wife Betty while attending Boston University. They dated for 2 years and graduated in ‘51 and ‘52 respectively. He entered the Navy upon graduation, attended OCS, and then was deployed to Korea aboard the USS Missouri. He and Betty married in ’53 and lived in the Norfolk, VA, area for a year while Ted finished his Navy service.

Dowell met his wife Betty while attending Boston University. They dated for 2 years and graduated in ‘51 and ‘52 respectively. He entered the Navy upon graduation, attended OCS, and then was deployed to Korea aboard the USS Missouri. He and Betty married in ’53 and lived in the Norfolk, VA, area for a year while Ted finished his Navy service.

Ted’s first knife making experience actually took place in high school shop class; but it shattered upon first use when he tried to chop a tree branch with it! It was in the USS Missouri’s machine shop, while in drydock in Norfolk, where he started to tinker in earnest. He hunted deer regularly, which fueled his need to find, or to make, a better edge-holding knife.

Ted’s first knife making experience actually took place in high school shop class; but it shattered upon first use when he tried to chop a tree branch with it! It was in the USS Missouri’s machine shop, while in drydock in Norfolk, where he started to tinker in earnest. He hunted deer regularly, which fueled his need to find, or to make, a better edge-holding knife.

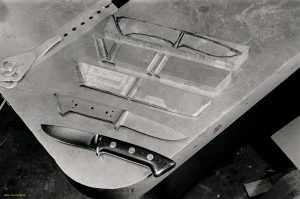

As detailed in John Lachuk’s 1974 Guns and Ammo Master Knifemaker article, Dowell made two knives while in Norfolk: a narrow tang, which was subsequently destroyed, and a full tang, which utilized a machine hacksaw blade and wood slab handles.

Upon his completion of active duty in the Navy, Ted and his newlywed bride moved to Oregon, where he put his educational background, including his master’s degree in mathematics, to good use. He landed a job as a high school math teacher in Madras, OR, and after a few years of getting settled in, he re-engaged in his passion for deer hunting.

It was during this time, the third Dowell knife was produced; A full tang, made in 1959, from a wood planer bit, and a handle of stag slabs from his first successful Oregon deer hunt. It was held together by two make-shift rivets crafted from .270 bullets, and surprisingly, the blade held an edge far better than anything Dowell’s previous efforts had produced. As a result, this became Ted’s primary using knife, but only for a year or two, as he continued to experiment with different steels; even as the family moved from Madras to Bend, OR, where Ted accepted a professorship in the Math Department at Central Oregon Community College (COCC).

Thankfully, all three of these initial Ted Dowell knives were saved by the maker. They are recognized for their historical significance as ‘the first three TMD’s ever produced’ and remain within the family collection to this day.

In 1966, Ted and family traveled to FL for a one-year sabbatical at Florida State University in Tallahassee. During that year, Dowell traveled to Bo Randall’s shop in Orlando, where he bought 2 heat-treated blades for which he planned to provide his own handles and sheaths. One for himself, and one for a close hunting buddy back in Oregon. This purchase turned out to have much greater significance than anyone realized at the time.

Once back home, Ted took the two Randall blades and installed his own hilts and handles on them, so they could be fully tested in field use. He also crafted his first ever leather sheaths for the knives. At the conclusion of their first season of use, which included the skinning and dressing of multiple mule deer, the two hunters were left ‘wanting something more’ in edge-holding capabilities.

As a result, Dowell decided it was time to try creating his own versions of the Randall knives, from scratch; this time, with his own choice of a (hopefully) superior edge-holding steel, and his own hand-ground blades. It turned out to be a cathartic event which changed the direction of his career. He remarked years later that the outcome of this “side-by-side comparison” gave him the needed confidence that he did, in fact, possess the skills necessary to make competitive handmade knives, and offer them for sale.

The significance of these knives and their accompanying sheaths was not lost on Betty, who held onto them for decades. Amazingly, 54 years later, Betty and son Jeff were able to track down the other Randall knife that Ted had given to his hunting buddy, and combine them all into an aggregate display piece that symbolizes the commercial genesis of TMD Knives.

The significance of these knives and their accompanying sheaths was not lost on Betty, who held onto them for decades. Amazingly, 54 years later, Betty and son Jeff were able to track down the other Randall knife that Ted had given to his hunting buddy, and combine them all into an aggregate display piece that symbolizes the commercial genesis of TMD Knives.

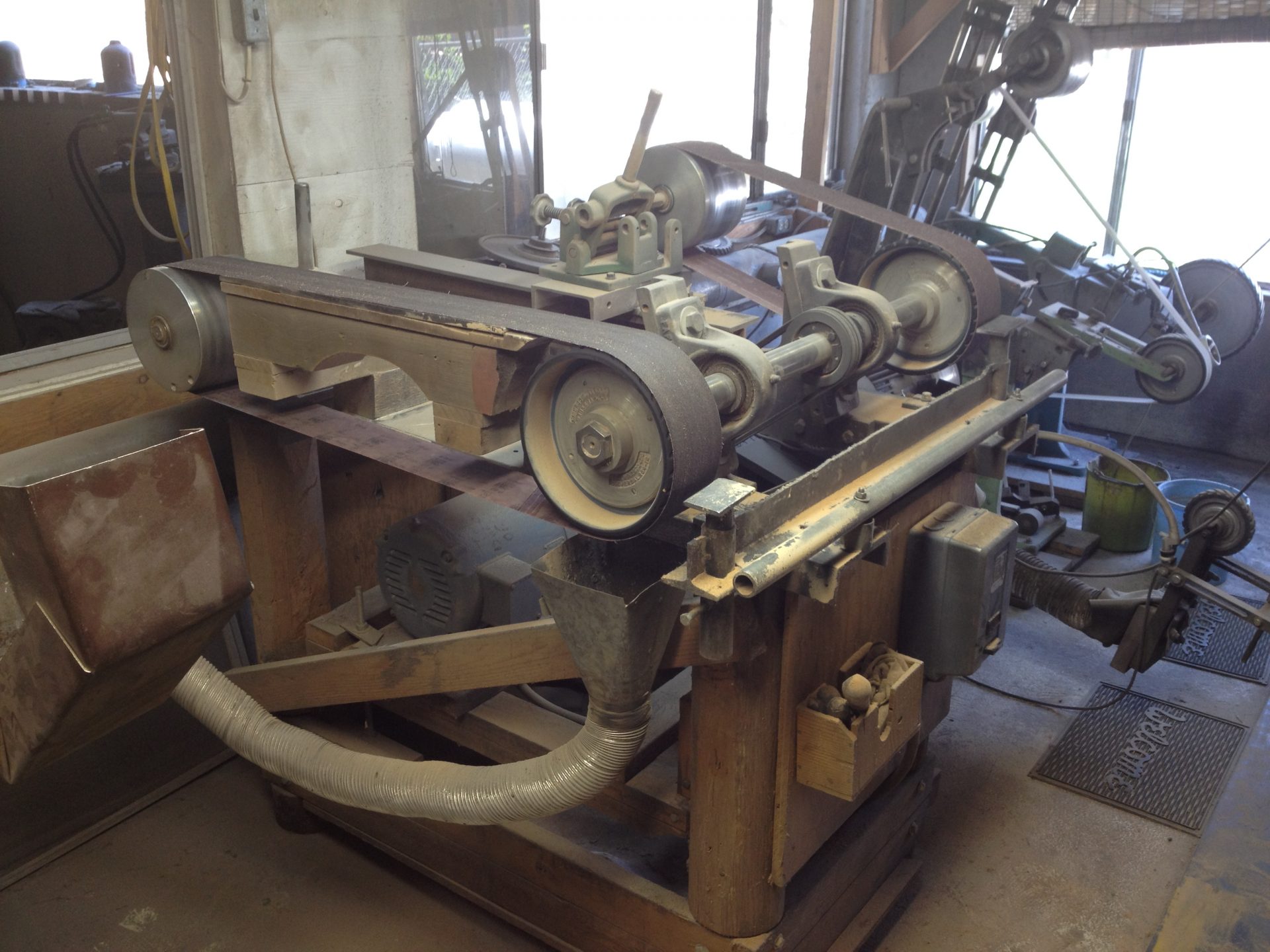

To support Ted’s endeavor into part-time knifemaking, the small two-car garage in the back yard of the family’s residence in Bend, Oregon, was converted to a full-time knifemaking shop. Sufficient 3 phase, 220v/110v AC power was brought in for the ensuing large equipment that was purchased or built. Over the 40 years of the shop’s full-time use, additions were made four more times. Once for a full-service buffing room, once for an expanded grinding room, once for a wood storage room, and lastly, once for a two-ton power hammer and forging station, complete with a 250 pound anvil and a 3,000-degree heat treating oven.

To support Ted’s endeavor into part-time knifemaking, the small two-car garage in the back yard of the family’s residence in Bend, Oregon, was converted to a full-time knifemaking shop. Sufficient 3 phase, 220v/110v AC power was brought in for the ensuing large equipment that was purchased or built. Over the 40 years of the shop’s full-time use, additions were made four more times. Once for a full-service buffing room, once for an expanded grinding room, once for a wood storage room, and lastly, once for a two-ton power hammer and forging station, complete with a 250 pound anvil and a 3,000-degree heat treating oven.

The accumulation of tools and supplies was ongoing, and on every spare wall hung thousands of dollars in grinding wheels and grinding belts of every imaginable size, shape, and grit. In some instances where Ted felt he needed an apparatus to accomplish a specific task, such as flat grinding a knife blade, he often designed and built a machine by himself, because he could find nothing in the marketplace that suited his needs!

Additional Shop and Machinery pictures can be found in Galleries, under the ‘Shop’ menu.

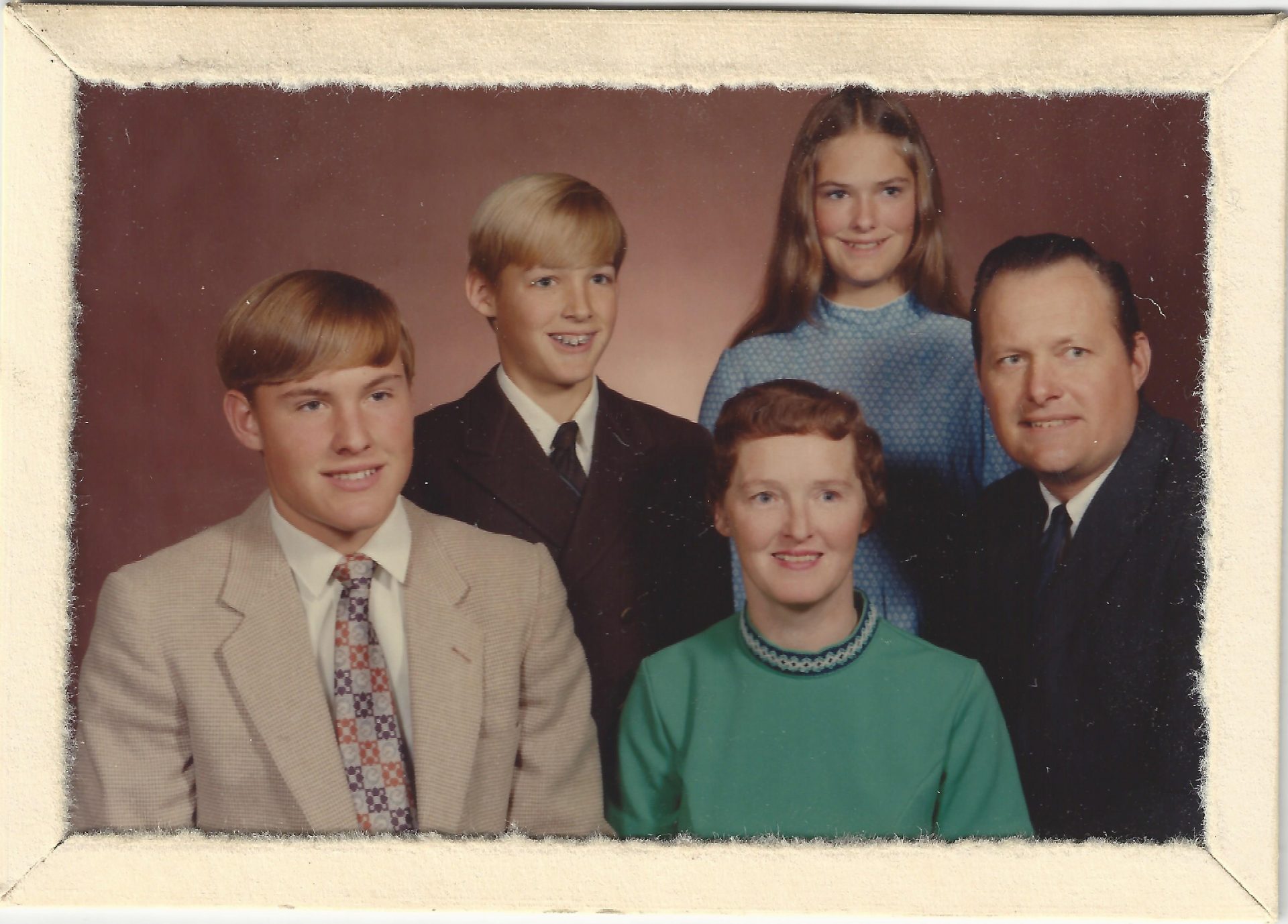

The early years in the business were a family affair. Ted made the knives. Oldest son Scott became the primary sheath maker during his high school and community college years. Daughter Lynn took care of starting the morning fire in the wood-burning stove that provided heat in the cold Central Oregon winter months. Youngest son Jeff, following in his siblings’ footsteps: started the morning fires, made sheaths, filed and sanded handles, and hand-rubbed flat ground blades. He also spent hundreds of hours operating the milling machine and metal bandsaw where the ‘stock removal’ work was performed on the early Integral Hilt and Integral Hilt and Cap hunting knives that Ted produced in the ‘70s.

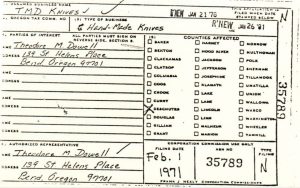

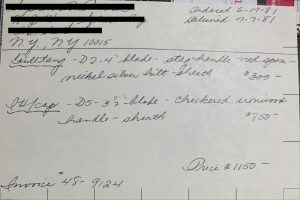

Wife Betty managed everything else in the business: inquiries and catalog request fulfillment, new catalog and price list creation, monthly newsletter creation and distribution, raw materials and supply purchasing, order tracking, shipping, as well as trade show planning, attendance, and logistics. For proper reference purposes, Betty also conceived, created and, for over 40 years, managed an order cataloging system that is still in use today. Her system utilized thousands of handwritten 4”x 6” index cards, all with the same categorical information regarding every knife ever ordered and shipped. On the right is a sample of what one looks like. So, if you have ever ordered and received a knife from TMD, there is a handwritten card in Betty’s file cabinets with your name on it!

Wife Betty managed everything else in the business: inquiries and catalog request fulfillment, new catalog and price list creation, monthly newsletter creation and distribution, raw materials and supply purchasing, order tracking, shipping, as well as trade show planning, attendance, and logistics. For proper reference purposes, Betty also conceived, created and, for over 40 years, managed an order cataloging system that is still in use today. Her system utilized thousands of handwritten 4”x 6” index cards, all with the same categorical information regarding every knife ever ordered and shipped. On the right is a sample of what one looks like. So, if you have ever ordered and received a knife from TMD, there is a handwritten card in Betty’s file cabinets with your name on it!

In those early years, it was commonplace within the Dowell household to open catalog requests (sent via US Mail using a six-cent stamp!) and find the requisite quarter taped to a piece of paper inside the envelope. If you look in the Catalog Archives section on this website, you can see the ‘25 Cents’ cost of the TMD catalog referenced on the cover of the 1970 edition.

In those early years, it was commonplace within the Dowell household to open catalog requests (sent via US Mail using a six-cent stamp!) and find the requisite quarter taped to a piece of paper inside the envelope. If you look in the Catalog Archives section on this website, you can see the ‘25 Cents’ cost of the TMD catalog referenced on the cover of the 1970 edition.

TMD Knives received its first order as a result of the placement of the only TMD display ad ever purchased; a ½” ad insert placed in American Rifleman magazine. The order came in June ‘68 from R. McKee, out of the Los Angeles area, for a Model 3 with a 7” blade; cost, $50. In that first year, 1450 catalogs were mailed, which contributed to 61 orders by year-end, 3 of which were a direct result of the initial Rifleman ad.

TMD Knives received its first order as a result of the placement of the only TMD display ad ever purchased; a ½” ad insert placed in American Rifleman magazine. The order came in June ‘68 from R. McKee, out of the Los Angeles area, for a Model 3 with a 7” blade; cost, $50. In that first year, 1450 catalogs were mailed, which contributed to 61 orders by year-end, 3 of which were a direct result of the initial Rifleman ad.

1968 – 1969: Ted, with very rare exception, had no markings on his knives during this period. Rather, he stamped a ‘TMD’ on the sheath, always in the same place, as can be seen here.

1968 – 1969: Ted, with very rare exception, had no markings on his knives during this period. Rather, he stamped a ‘TMD’ on the sheath, always in the same place, as can be seen here.

1970: At some point during this year a TMD stamp was used to imprint the hilt of the knife, except for those knives which had no hilt, in which case either the sheath marking sufficed, or in very few cases, the TMD was stamped on the handle somewhere. Some knives from this era, with hilts, had the TMD on both the hilts and the sheath.

1971-1974: This was the period when each TMD was inscribed with a serial number, using the format of:

1971-1974: This was the period when each TMD was inscribed with a serial number, using the format of:

Year Made / Knife # Sold in That Year / Type of Steel

The Type of Steel Designations were:

| A=A2 | C=440 | F=F8 | D2=D2 |

| D3=D3 | S=S5 | SM=S5 (Loveless modified) | |

| M2=M2 | B=VascoBB | ST=Staminal | |

| CM=154CM | V=VersaSteel | ||

For TMD’s that have serial numbers inscribed on them, the numbers should fall between the ranges shown here:

1971 (88) 71-1-F to 71-88-D2

1972 (95) 72-1-M2 to 72-95-M2

1973 (220) 73-1-ST to 73-220-D2

1974 (10) 74-1-D2… 11, 12 … 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 …47, to 74-48-D2

From roughly 1973 going forward: The TMD Escutcheon became the only marking used – a picture of the first knife on which Ted used an escutcheon can be seen here. The only circumstances where an escutcheon was not always used was on some Art Knives, and some very rare, totally custom-design pieces where the ‘button’ simply couldn’t be used. In these cases, there was always an engraved ‘TMD’ or ‘Ted Dowell’ or ‘Ted Dowell Bend Oregon’, somewhere on the knife or the sheath.

From roughly 1973 going forward: The TMD Escutcheon became the only marking used – a picture of the first knife on which Ted used an escutcheon can be seen here. The only circumstances where an escutcheon was not always used was on some Art Knives, and some very rare, totally custom-design pieces where the ‘button’ simply couldn’t be used. In these cases, there was always an engraved ‘TMD’ or ‘Ted Dowell’ or ‘Ted Dowell Bend Oregon’, somewhere on the knife or the sheath.

(Note 1: The only additional steels used by TMD beyond 1974 were: BG-42 & Vascowear.

(Note 2: The only numbers on file for ’74 are shown above, indicating that we may have incomplete records. There may be TMDs marked 74-13-…-31- and … 37…46 out there somewhere, and we don’t know it – so tell us if you have one!

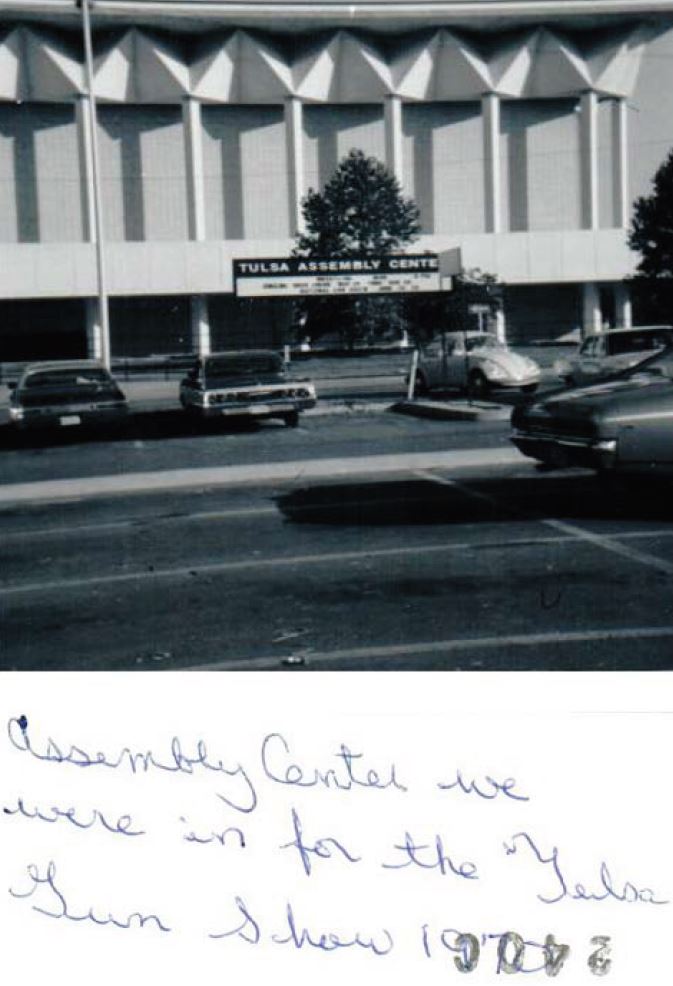

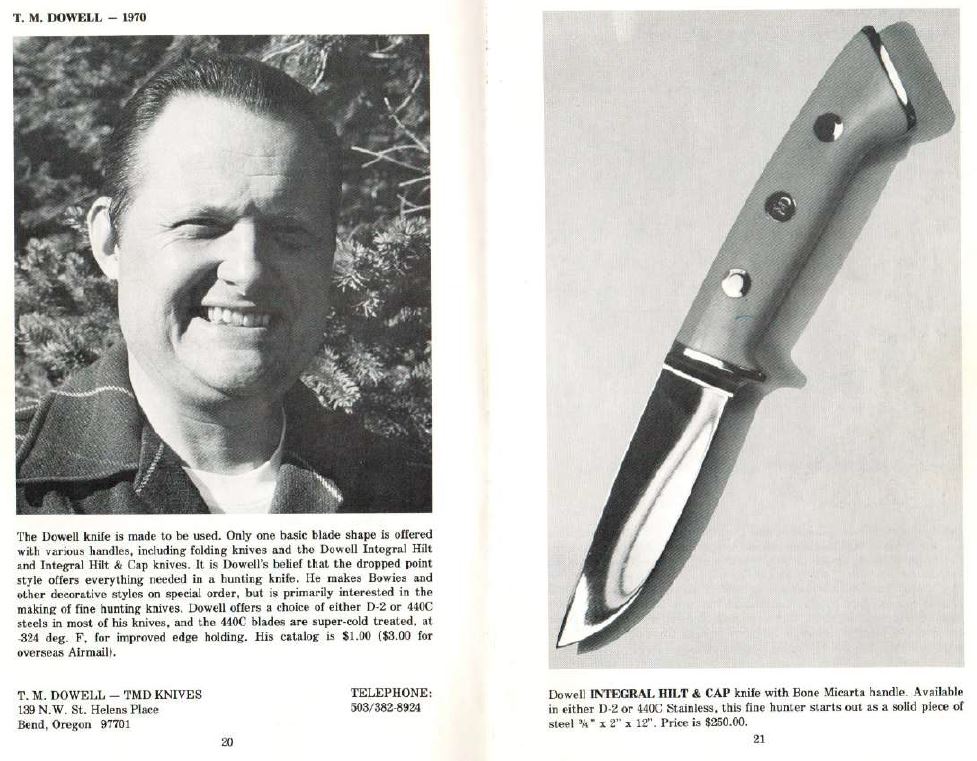

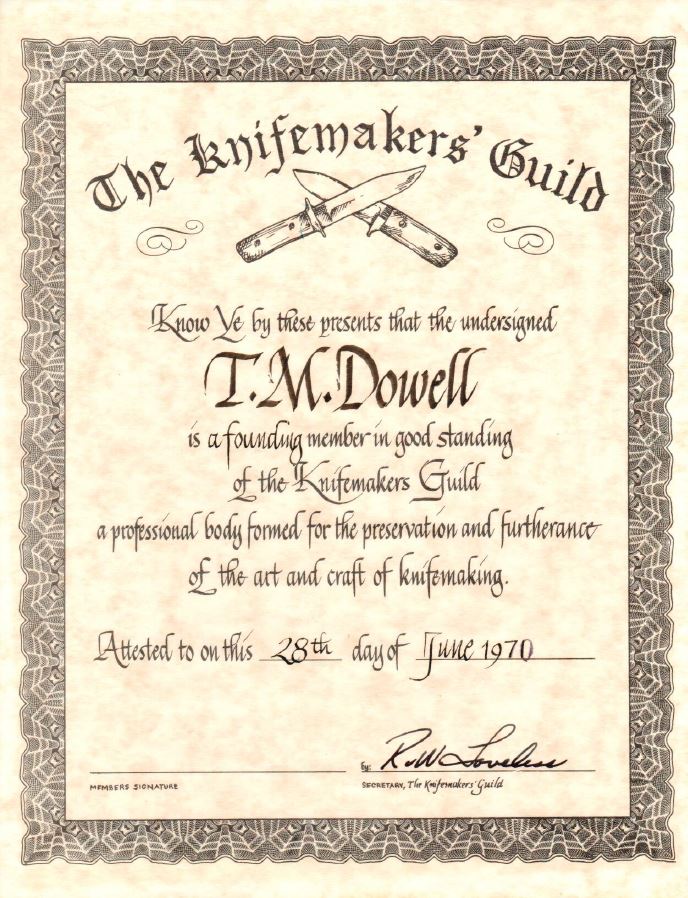

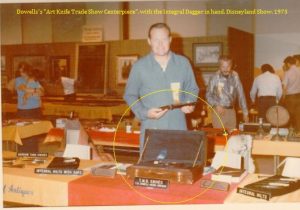

In the early ‘70s, when Ted and Betty started attending trade shows, knifemakers had to go to ‘combo shows’, where firearms were typically the mainstay of the event. The custom knifemakers were somewhat ancillary and all located within a common area on the trade show floor. TMD’s first trade show was the Tulsa National Antique Gun Show in 1970. You can see a picture of the Tulsa venue, taken by Betty, here. This show, with its 11 founding members, marked the official formation of ‘The Knifemakers Guild’. Ted’s ‘Founding Member’ certificate and Guild Directory Profile are featured below.

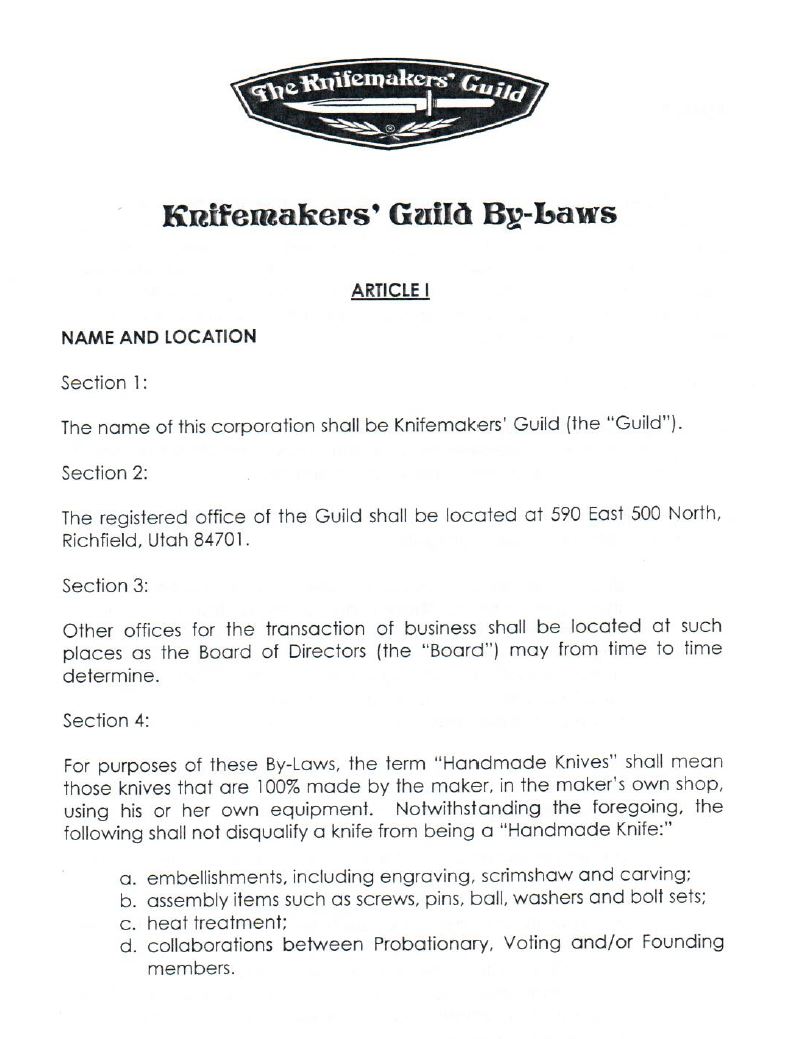

It was at the 1972 Guild show at the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City that the bylaws of the Guild, crafted in ’71-‘72 by Bob Loveless and Ted Dowell, were presented to, and adopted by, the general membership of the Guild. The creation of the By-Laws was the result of many iterations between the two men, with Betty still having the original handwritten pages containing all the edits, additions, deletions, etc., that took place as part of arriving at the final version.

For an in-depth history, compiled by Bob Loveless, of the early formation of the KMG, the Maker profiles of the Founding Members, and a copy of the original bylaws, see the Archives and Reference area of this site. The guild still exists today and has an active membership. The website can be found at https://knifemakersguild.com

In late 1970, Ted was struggling with getting enough orders to sustain the business. One area he thought there might be more opportunity (i.e., more sales) was in the creation of a very basic, easy/quick to make, ultra-low-cost knife. As a result, the Model 8 was born; a narrow tang with a hardwood handle, a brushed-finish-only blade, and a shocking price tag of $20, which included a sheath! Surprisingly, the Model 8 was not a big seller. Fortunately for Dowell, just after the Model 8 was announced, order volumes picked up for many of his standard models, and TMD Knives took off from there.

In late 1970, Ted was struggling with getting enough orders to sustain the business. One area he thought there might be more opportunity (i.e., more sales) was in the creation of a very basic, easy/quick to make, ultra-low-cost knife. As a result, the Model 8 was born; a narrow tang with a hardwood handle, a brushed-finish-only blade, and a shocking price tag of $20, which included a sheath! Surprisingly, the Model 8 was not a big seller. Fortunately for Dowell, just after the Model 8 was announced, order volumes picked up for many of his standard models, and TMD Knives took off from there.

Bob Loveless popularized the full-tang design, and until Dowell and Loveless got together at Bob’s shop in Riverside, CA in 1970, Dowell had only produced hidden-tang knives. It was during this visit that he learned how to make the full-tang knife, which led to the introduction of several such models in Ted’s next catalog. ‘The Dowell Knife’ as coined by John Lachuk, in his 1974 Guns & Ammo article, was Ted’s full-tang dropped point design, and to Lachuk, became the ‘defining look’ for most TMD knives. Dowell continued to refine and re-apply this simplistically elegant design, which is a stalwart for hunting and utility knives made by dozens, if not hundreds, of makers today.

Bob Loveless popularized the full-tang design, and until Dowell and Loveless got together at Bob’s shop in Riverside, CA in 1970, Dowell had only produced hidden-tang knives. It was during this visit that he learned how to make the full-tang knife, which led to the introduction of several such models in Ted’s next catalog. ‘The Dowell Knife’ as coined by John Lachuk, in his 1974 Guns & Ammo article, was Ted’s full-tang dropped point design, and to Lachuk, became the ‘defining look’ for most TMD knives. Dowell continued to refine and re-apply this simplistically elegant design, which is a stalwart for hunting and utility knives made by dozens, if not hundreds, of makers today.

The inclusion of full-tang knives into TMD’s repertoire not only led to the sale of over a thousand such knives, but also set the stage for a far more important innovation, which most writers and collectors acknowledge cemented Dowell’s legacy in custom knifemaking history – the creation of the Dowell Integral.

The TMD Integral came about when Ted reached for a screwdriver in his shop, and as fate would have it, he picked up one of two 40+ year old screwdrivers that he kept from his youth as a mechanic. He recalled there was something unusual about the screwdrivers, but because he used them on such a regular basis, he thought nothing of it. This time however, he took a closer look. It was then that he remembered they were actually made of a single piece of steel, with slab handles on each side – and it was there that the ‘ah-ha!’ moment occurred.

The TMD Integral came about when Ted reached for a screwdriver in his shop, and as fate would have it, he picked up one of two 40+ year old screwdrivers that he kept from his youth as a mechanic. He recalled there was something unusual about the screwdrivers, but because he used them on such a regular basis, he thought nothing of it. This time however, he took a closer look. It was then that he remembered they were actually made of a single piece of steel, with slab handles on each side – and it was there that the ‘ah-ha!’ moment occurred.  “What if I took this same concept and made a full-tang knife that way?” And with that, the TMD Integral was born. The ‘one-piece knife’ first took form as a wooden proof-of-concept piece but was followed almost immediately with Ted’s first actual Integral Hilt knife. A picture of these two historical creations can be seen here.

“What if I took this same concept and made a full-tang knife that way?” And with that, the TMD Integral was born. The ‘one-piece knife’ first took form as a wooden proof-of-concept piece but was followed almost immediately with Ted’s first actual Integral Hilt knife. A picture of these two historical creations can be seen here.

A few dozen Integral Hilt dropped point hunters were initially created, but within a year of the initial design’s debut, Ted added an Integral Cap as well, which hit the market in early ’72. Here is a pictorial sequence of how Ted made his Integrals. The Integral Hilt and Cap became a fundamental TMD design that was produced by the hundreds for both using knives as well as high-end art pieces.

A few dozen Integral Hilt dropped point hunters were initially created, but within a year of the initial design’s debut, Ted added an Integral Cap as well, which hit the market in early ’72. Here is a pictorial sequence of how Ted made his Integrals. The Integral Hilt and Cap became a fundamental TMD design that was produced by the hundreds for both using knives as well as high-end art pieces.

An important side note here: Ted never claimed to have invented the Integral design. He did, however, re-introduce it to modern custom knifemaking, and to a large degree, popularized it, such that multiple makers now offer the Integral design. Dowell knew, from his research, that English cutlers had long ago made kitchen knives with integral hilts. But as Phil Lobred said in 2004:

“…Ted’s integrals are wonderful…He basically invented what we know as the Integral knife today.”

Used with permission: BLADE® Magazine and blademag.com

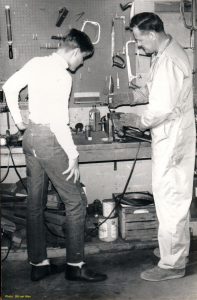

In 1971 and 1973, both of Dowell’s sons were working with their father in the shop. During each of those periods Ted sat down with them and asked that they agree to work with him in an exercise he called “making your first knife”. Ted pledged his support in the form of “You get to decide what model of knife you want to make. Then I will show you first how to do each step, then you will try it on your own, and when and if you ask for help, I will assist. In the end, you, for the most part, will have produced your first knife!”

Scott chose to make a narrow tang bowie shaped knife, which had a brass hilt and a greenish blue synthetic handle material called Delrin, while Jeff chose to make his personal ‘favorite’ at the time, the entry-level Model 8.

The processes took each son roughly a week to complete, and clearly, given the quality of the outcome, not to mention the young ages of the two, Ted obviously provided a great deal of “support” and influenced the respective outcomes accordingly. The two knives were not marked “TMD”, but instead, were etched with the name of each son at the top of each blade. Though the etchings have worn down over the decades, they remain visible to this day. Accompanying sheaths were also co-produced and remain with each knife.

In the early ‘70s, other custom makers started experimenting with this material, but Dowell was not impressed by the look nor the degrading impact he felt the use of such a material had on a handmade knife.

He was goaded by friend Phil Lobred about his ‘position’ on the matter to the degree that he finally decided to make one, just to “shut Lobred up.” To add fuel to the (friendly) fire, when Ted privately showed Lobred the knife, he referred to it disparagingly as his first “Mother of Toilet Seat” knife. In fact, he disliked it so much, he refused to put any TMD markings of any kind on it and immediately thereafter, stuffed it away in a shoebox, where it was discovered 45 years later by family members.

As fate would have it, Dowell begrudgingly agreed a few years later to make a ‘miniature’ Integral hilt knife with the same handle material for a long-time customer who begged him repeatedly to do so. Ironically, a picture of the knife, along with two other integrals, made it into Dowell’s June 1976 Catalog, but not without Ted wryly placing the picture on ‘unlucky’ page 13 in addition to calling out the unique handle in the picture caption as “Not a good handle material”.

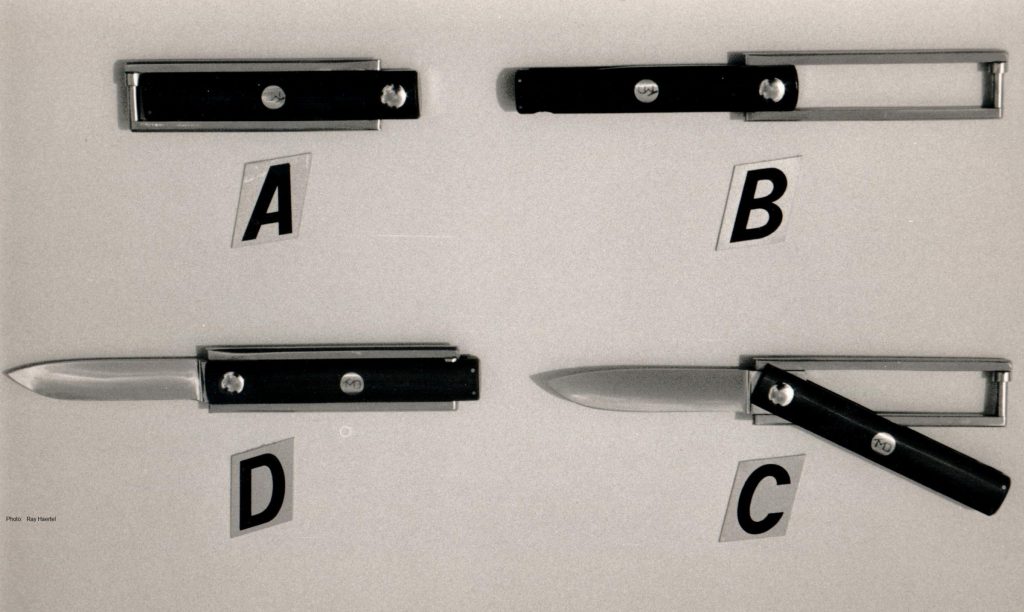

Like the Integral Hilt and Cap design, the TMD ‘Funny Folder’ was not invented by Ted. But like the Integral, it was certainly popularized by him. Dowell was given a small all-metal ‘promotional’ knife by a friend which served as the basis for his design – essentially, a larger version, but with modern-day improvements. Here is an example of how the folder opens and closes, as well as the 3 sizes that TMD made.

The Funny Folder was featured in an Article from Gun Digest Book of Folding Knives in 1977 entitled, Most Unique Folding Knives. Pictures from a private collection of most all of the various types of locking mechanisms that Ted experimented with for the Funny Folder can be seen here.

The Funny Folder was featured in an Article from Gun Digest Book of Folding Knives in 1977 entitled, Most Unique Folding Knives. Pictures from a private collection of most all of the various types of locking mechanisms that Ted experimented with for the Funny Folder can be seen here.

In the early ‘70s, Ted and Betty’s days were long and their nights, short. When one considers the increase in the quality of the workmanship from ’70 to ’74, the growing breadth of Ted’s product offerings, and the innovative efforts required to create The Dowell Knife, The Integral, and The Funny Folder, a picture begins to emerge. Combine all that with the efforts put forth by Ted (and others) to get the Guild formed and operational, and finally, realizing that all this was done while still being a full-time mathematics professor, one gets a sense of the magnitude of the effort that must have been expended!

In the early ‘70s, Ted and Betty’s days were long and their nights, short. When one considers the increase in the quality of the workmanship from ’70 to ’74, the growing breadth of Ted’s product offerings, and the innovative efforts required to create The Dowell Knife, The Integral, and The Funny Folder, a picture begins to emerge. Combine all that with the efforts put forth by Ted (and others) to get the Guild formed and operational, and finally, realizing that all this was done while still being a full-time mathematics professor, one gets a sense of the magnitude of the effort that must have been expended!

Thus, in June of ‘74, at the age of 46, he resigned his professorship, left teaching behind, and went full-time into the knife business. This was a bold move, but Ted always followed his heart, and though both his parents and his in-laws expressed concerns about leaving the security and tenure of a college professorship, they knew their son-in-law well enough to know there’d be no turning back!

Thus, in June of ‘74, at the age of 46, he resigned his professorship, left teaching behind, and went full-time into the knife business. This was a bold move, but Ted always followed his heart, and though both his parents and his in-laws expressed concerns about leaving the security and tenure of a college professorship, they knew their son-in-law well enough to know there’d be no turning back!

It is said that the death of a child is the most traumatic event a parent can experience. The Dowell family lost oldest son Scott on May 16, 1975, in a car accident at 19 years of age.

It is said that the death of a child is the most traumatic event a parent can experience. The Dowell family lost oldest son Scott on May 16, 1975, in a car accident at 19 years of age.

Scott spent countless hours with Ted working in the shop on a variety of tasks as a young man. But ultimately, he found sheath making and working with leather to be his passion. He was the sole TMD sheath maker from 1970 to 1975, producing roughly five hundred sheaths over that period. He also dabbled in artistic leather-related activities, such as the hand-tooled inscribing of various patterns and scenes into the surface of the leather.

Prior to his expected departure for Willamette University in the Fall of 1975, Scott and Ted decided to create a set of 3 ‘miniature’ knives that were designed to fit unobtrusively onto handmade inscribed belts with accompanying sheaths. The resulting pieces were completed and photographed in late April, just weeks before Scott’s passing.

Prior to his expected departure for Willamette University in the Fall of 1975, Scott and Ted decided to create a set of 3 ‘miniature’ knives that were designed to fit unobtrusively onto handmade inscribed belts with accompanying sheaths. The resulting pieces were completed and photographed in late April, just weeks before Scott’s passing.

He is deeply missed by his family and friends to this day…

The show, held at the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City, MO, with Ted as President of the Guild, was considered by some to be a risky venture. It would be a first-of-its-kind, where only knifemakers were present, unlike the combination gun/knife shows of the past. It was envisioned, promoted, and successfully executed by Dowell, and it marked a turning point for custom knifemaking. It helped to establish the credibility and growth of both the Guild, as well as its show. It also bolstered the custom knives genre overall, by creating a singular annual tradeshow of record, where knifemakers, collectors and dealers from around the world gathered for decades to come.

After a few Guild shows were held under this new format, Ted learned that some KMG members felt his ‘solo’ format might be limiting the Guild’s growth opportunities. As a result, conversations started amongst members who were considering not attending the show the following year. Fearing the negative impact even a few of the better-known makers’ absences would have on the show, Ted wrote a letter to all KMG members, encouraging them to ‘stay the course’ and keep the Guild’s advancements and prominence intact. A copy of that letter can be found to the right. The letter, accompanied by many phone calls, helped to cement the ‘knifemakers and associate members only’ approach, which remained the primary format for the KMG Show for decades.

After a few Guild shows were held under this new format, Ted learned that some KMG members felt his ‘solo’ format might be limiting the Guild’s growth opportunities. As a result, conversations started amongst members who were considering not attending the show the following year. Fearing the negative impact even a few of the better-known makers’ absences would have on the show, Ted wrote a letter to all KMG members, encouraging them to ‘stay the course’ and keep the Guild’s advancements and prominence intact. A copy of that letter can be found to the right. The letter, accompanied by many phone calls, helped to cement the ‘knifemakers and associate members only’ approach, which remained the primary format for the KMG Show for decades.

Between 1970 and 2009 Ted and Betty attended 40 consecutive KMG Shows. And though there were changes of venues over the decades, they never missed a single show! To the right is a picture from that final show in Louisville, KY.

Between 1970 and 2009 Ted and Betty attended 40 consecutive KMG Shows. And though there were changes of venues over the decades, they never missed a single show! To the right is a picture from that final show in Louisville, KY.

With Ted’s passing in Oct of 2012, John Owens, currently residing in Buena Vista, CO, became the lone surviving founding member of the Knifemakers Guild. As of February 2021, this still holds true.

In the early ‘70s, Ted fancied himself a premier Using Knifemaker, not an Art Knifemaker. In 1973, at one show after another, Ted watched intently as other makers, in addition to showing their hunting knives, were showing large format Bowie knives, which featured elaborate engraving and/or scrimshawed handles. Those makers were overwhelmed with buyers for that genre of knife, and Ted, not wanting to be left out, decided it was time to make his own ‘Presentation Set’ for a trade show centerpiece. In a matter of months,

In the early ‘70s, Ted fancied himself a premier Using Knifemaker, not an Art Knifemaker. In 1973, at one show after another, Ted watched intently as other makers, in addition to showing their hunting knives, were showing large format Bowie knives, which featured elaborate engraving and/or scrimshawed handles. Those makers were overwhelmed with buyers for that genre of knife, and Ted, not wanting to be left out, decided it was time to make his own ‘Presentation Set’ for a trade show centerpiece. In a matter of months,  Dowell created not only a classic Integral Hilt Bowie, but an accompanying Integral Hilt Fighting Knife as well. He had them both engraved by master engraver Henry Frank, and as a finishing touch, Dowell hand-crafted a matching display box for the two knives! Because he didn’t really want to sell the set (and lose his centerpiece), Dowell purposely put what he considered to be the outrageous price of $3,000 on it. After a few years of use, Ted decided to designate the piece his ‘first Art Knife piece’ and retire it as a family heirloom. A picture of the stand-alone knives can be seen to the right and of the full display piece here.

Dowell created not only a classic Integral Hilt Bowie, but an accompanying Integral Hilt Fighting Knife as well. He had them both engraved by master engraver Henry Frank, and as a finishing touch, Dowell hand-crafted a matching display box for the two knives! Because he didn’t really want to sell the set (and lose his centerpiece), Dowell purposely put what he considered to be the outrageous price of $3,000 on it. After a few years of use, Ted decided to designate the piece his ‘first Art Knife piece’ and retire it as a family heirloom. A picture of the stand-alone knives can be seen to the right and of the full display piece here.

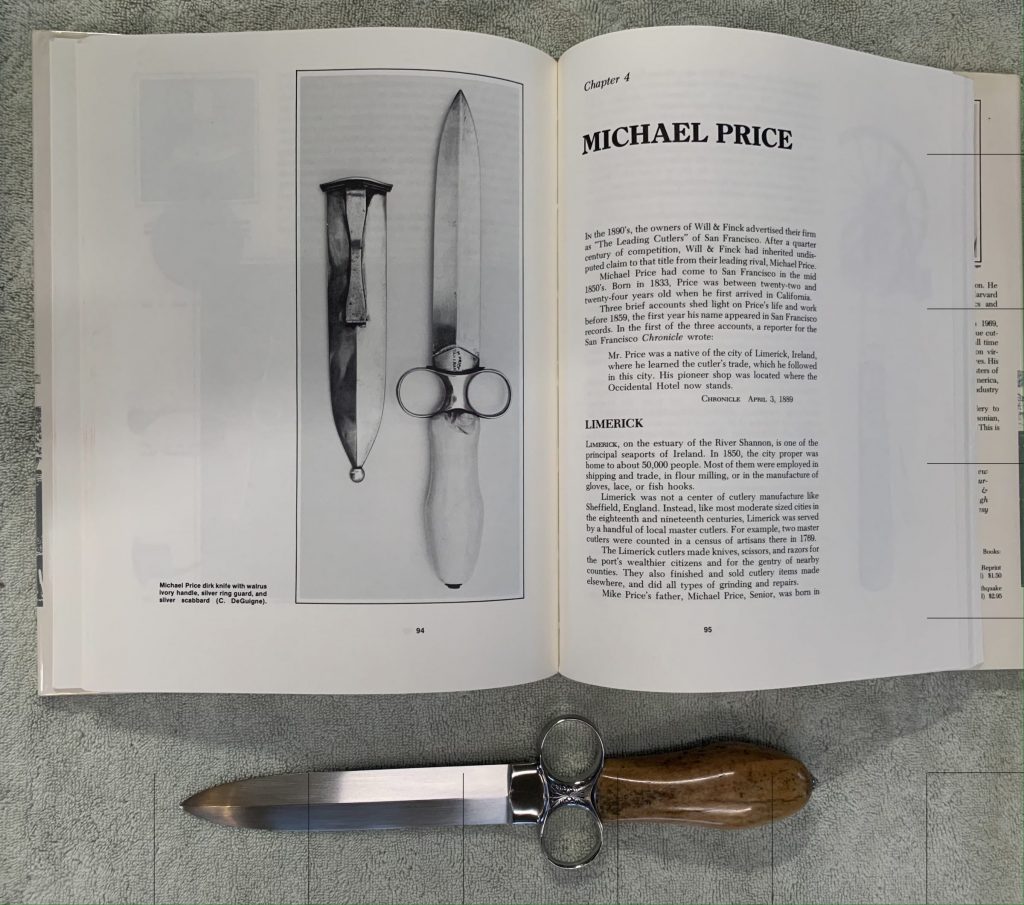

In 1977, Dowell’s second venture into Art Knives came when collector, Phil Lobred, commissioned him to make an Integral Michael Price Bradford Dagger. Dowell produced and delivered what Lobred immediately designated as a ‘breakthrough piece’, because it not only incorporated Ted’s Integral design for the Hilt and the Cap but also elegantly extended it to include the entire metal handle ‘wrap’. This piece debuted at the ’78 New York Custom Knives Show, where it won “Best of Show”, and was subsequently used in several promotional brochures for years after its completion.

In, or around 1980, Dowell was notified that two of his knives had been selected by the Institute for inclusion into their American History Museum. One was a Funny Folder, the other an Integral Hunter, engraved Henry Frank. The knives are available for viewing on a cyclical basis, as scheduled by the Smithsonian. Upon word of this reaching Ted, he was both humbled and deeply appreciative. After all, not many knifemakers of that period can share in this distinction!

In, or around 1980, Dowell was notified that two of his knives had been selected by the Institute for inclusion into their American History Museum. One was a Funny Folder, the other an Integral Hunter, engraved Henry Frank. The knives are available for viewing on a cyclical basis, as scheduled by the Smithsonian. Upon word of this reaching Ted, he was both humbled and deeply appreciative. After all, not many knifemakers of that period can share in this distinction!

The AKI was the brainchild of Phil Lobred, modeled after the wildly successful ‘Cowboy Artists of America’ show that Phil often attended. Lobred’s game-changing vision was to create a knife show with a similar format and execution as the Cowboy Artists, where most art pieces were secured via ‘intent to bid’ submissions, with only one bidder ultimately being drawn and receiving the first right of refusal on the piece.

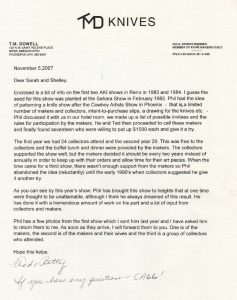

The AKI would take that same basic approach but would be ‘personalized’ for the custom knifemaking artists and collectors. As noted in this letter from Betty Dowell to Shelly and Sarah Berman, Ted and Betty spent many hours during the formative years of the AKI working with Lobred to help craft some of the framework and operational logistics around his vision. The first two AKI’s were held in ’83 and ’84, both taking place in Reno, NV. At the conclusion of the ’84 show, when Lobred reached out to the invited makers to solicit interest (and early deposits) for an ’85 show, Phil received a less than encouraging response, and as you can see in this letter, the show was not held again until 1993, after both collectors and makers encouraged him to restart the event. The ’93 show was a huge success, and the show’s biennial format change (as requested by the makers) gave everyone the requisite time to create the typical three to six high-end Art Knives necessary to make a respectable showing at each event.

The AKI would take that same basic approach but would be ‘personalized’ for the custom knifemaking artists and collectors. As noted in this letter from Betty Dowell to Shelly and Sarah Berman, Ted and Betty spent many hours during the formative years of the AKI working with Lobred to help craft some of the framework and operational logistics around his vision. The first two AKI’s were held in ’83 and ’84, both taking place in Reno, NV. At the conclusion of the ’84 show, when Lobred reached out to the invited makers to solicit interest (and early deposits) for an ’85 show, Phil received a less than encouraging response, and as you can see in this letter, the show was not held again until 1993, after both collectors and makers encouraged him to restart the event. The ’93 show was a huge success, and the show’s biennial format change (as requested by the makers) gave everyone the requisite time to create the typical three to six high-end Art Knives necessary to make a respectable showing at each event.

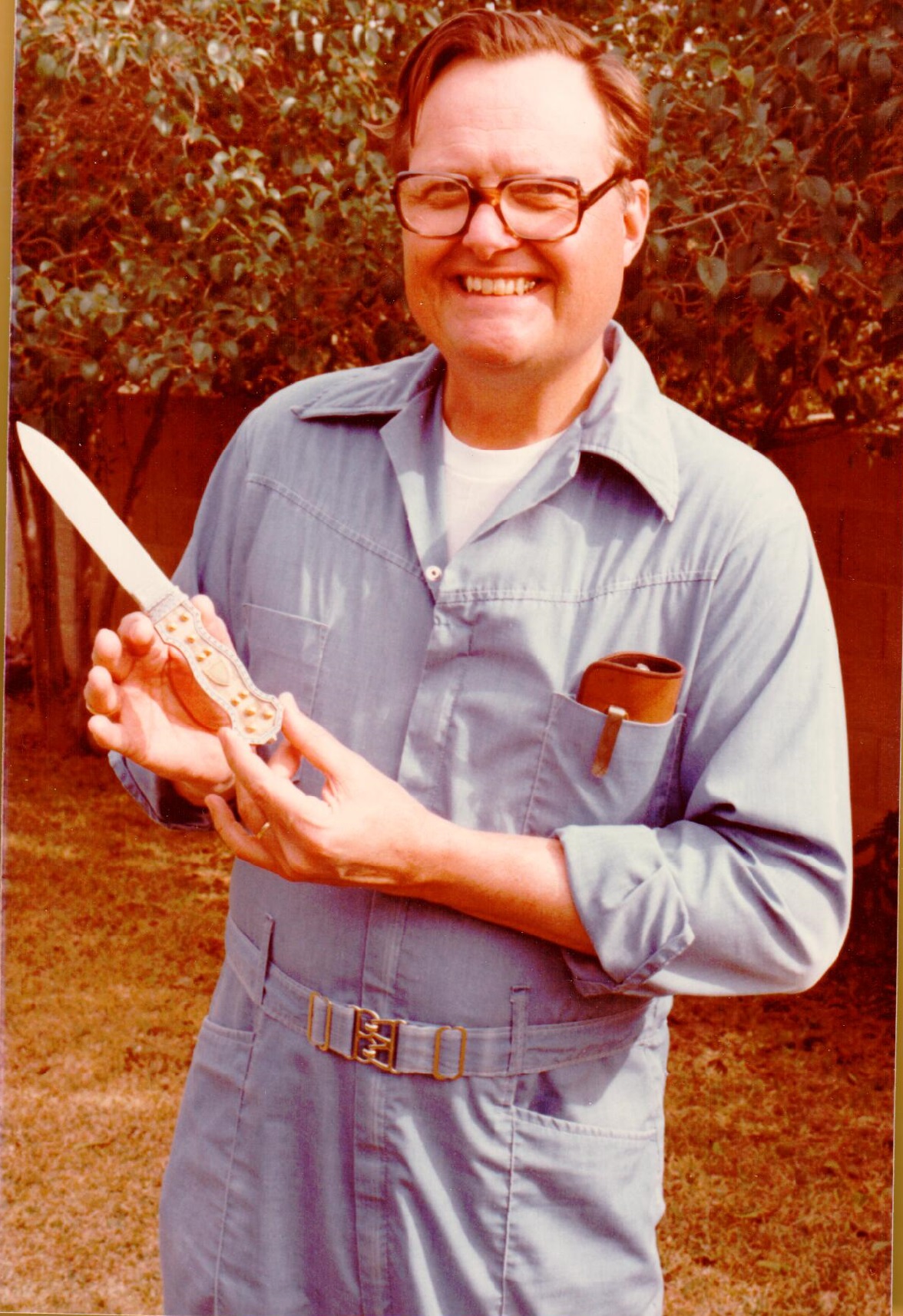

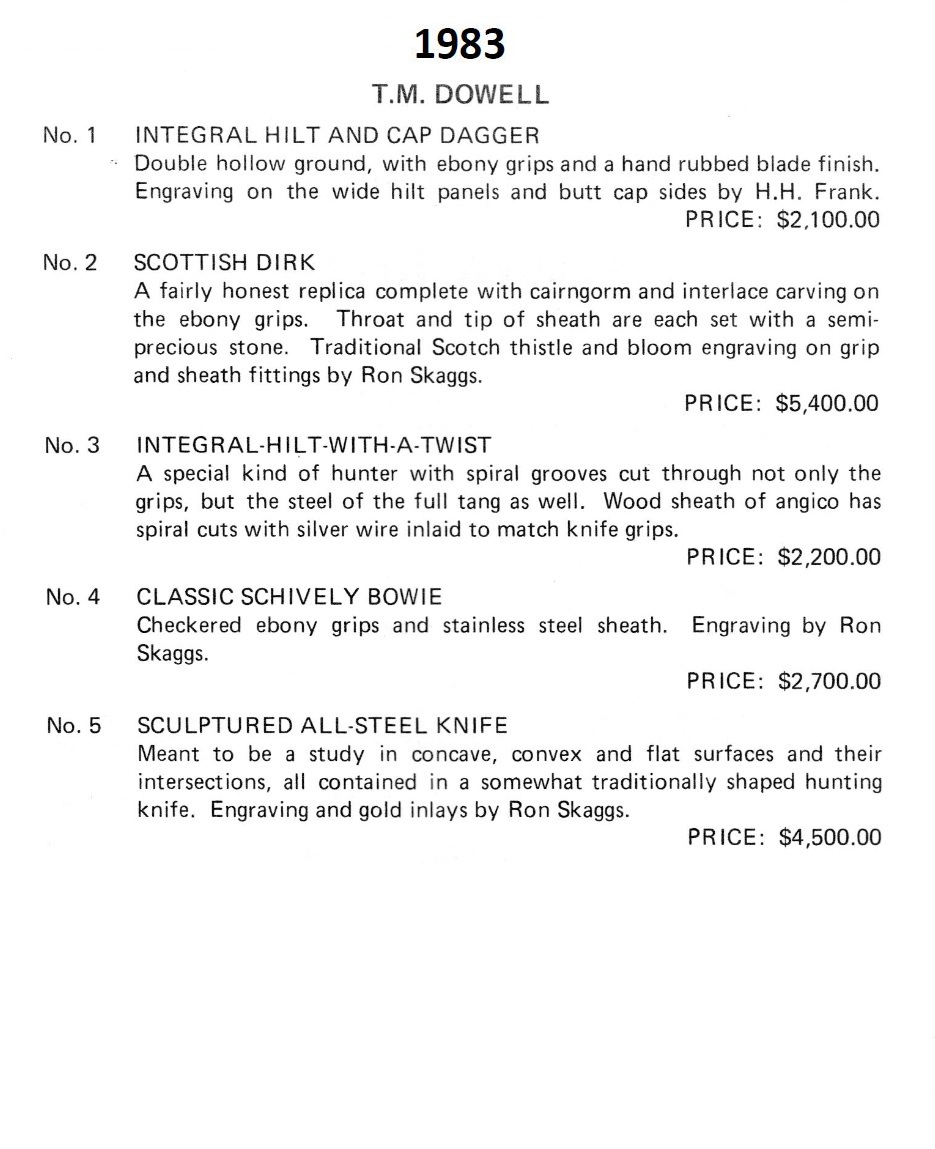

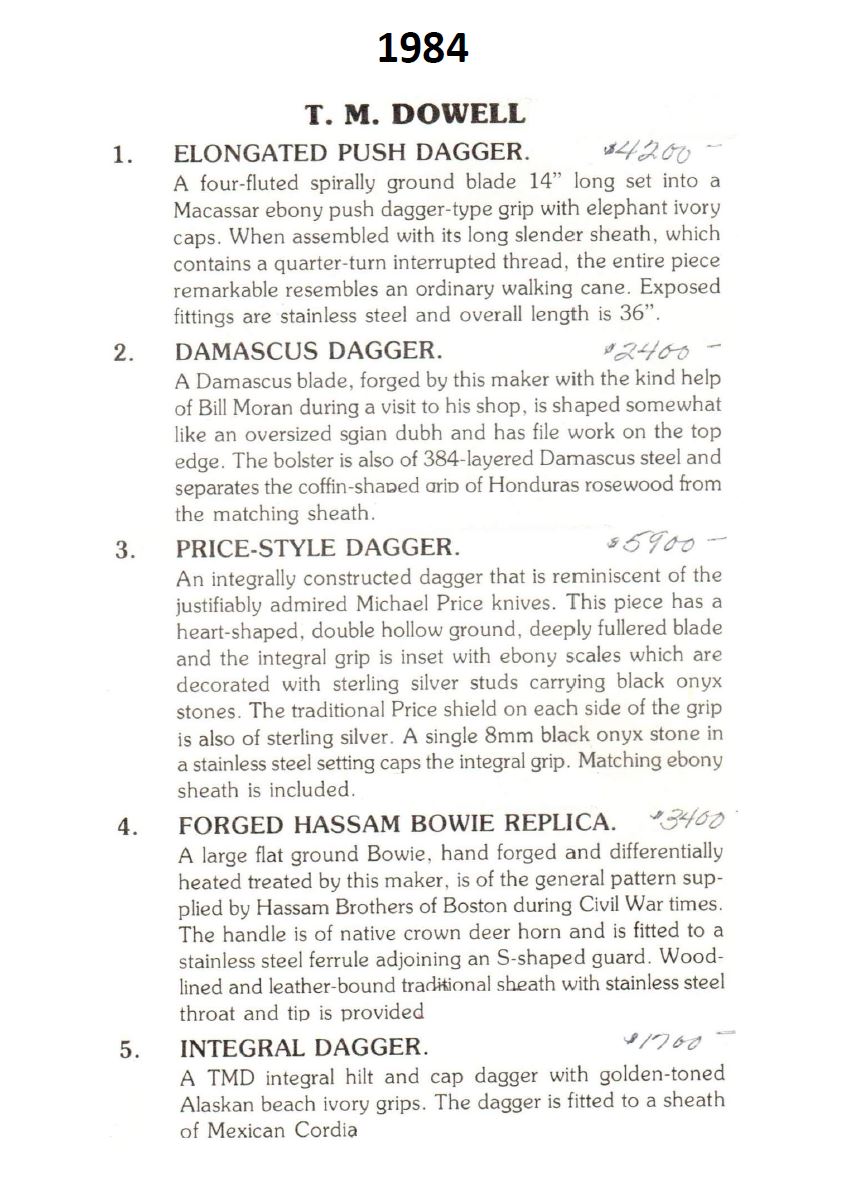

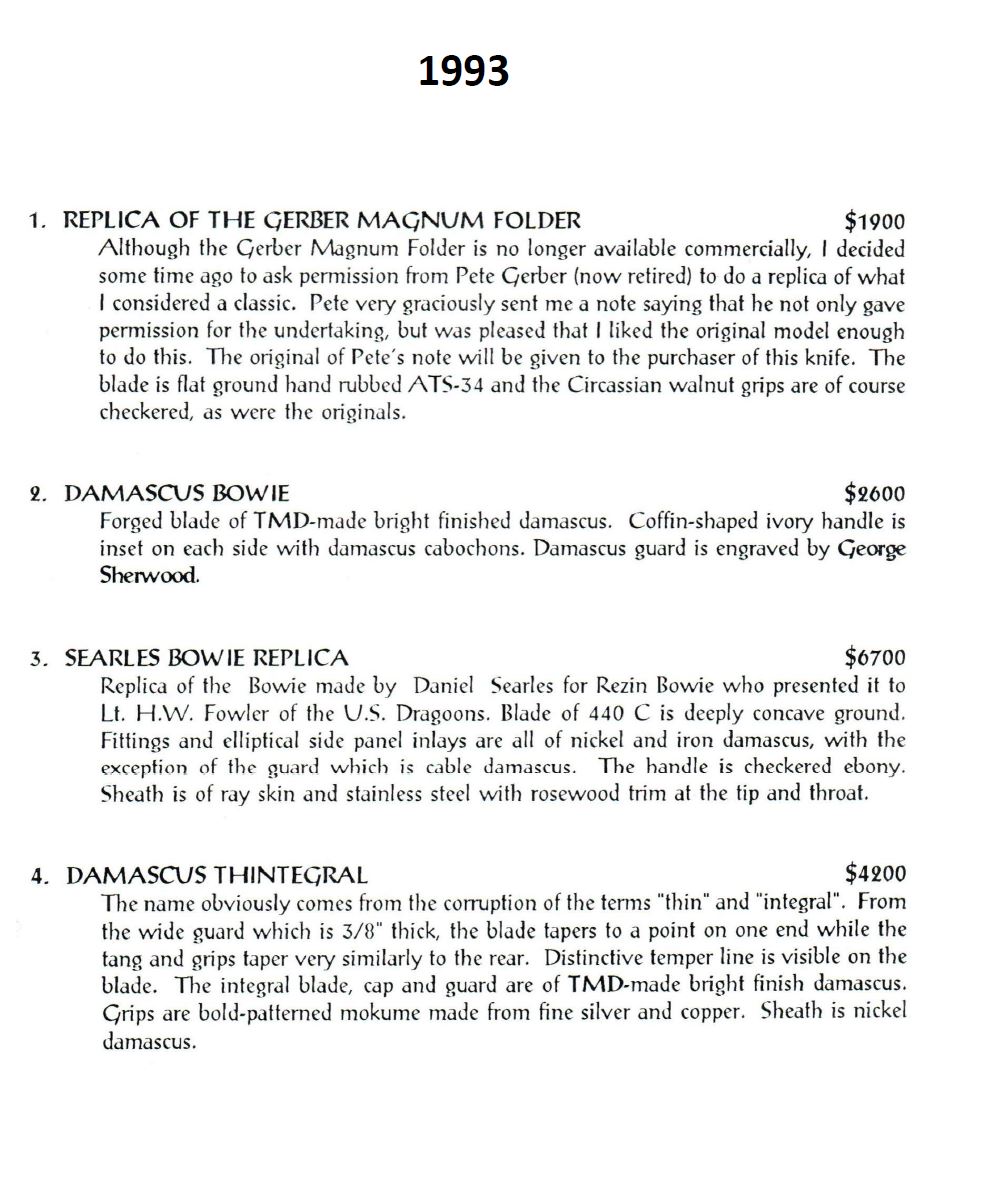

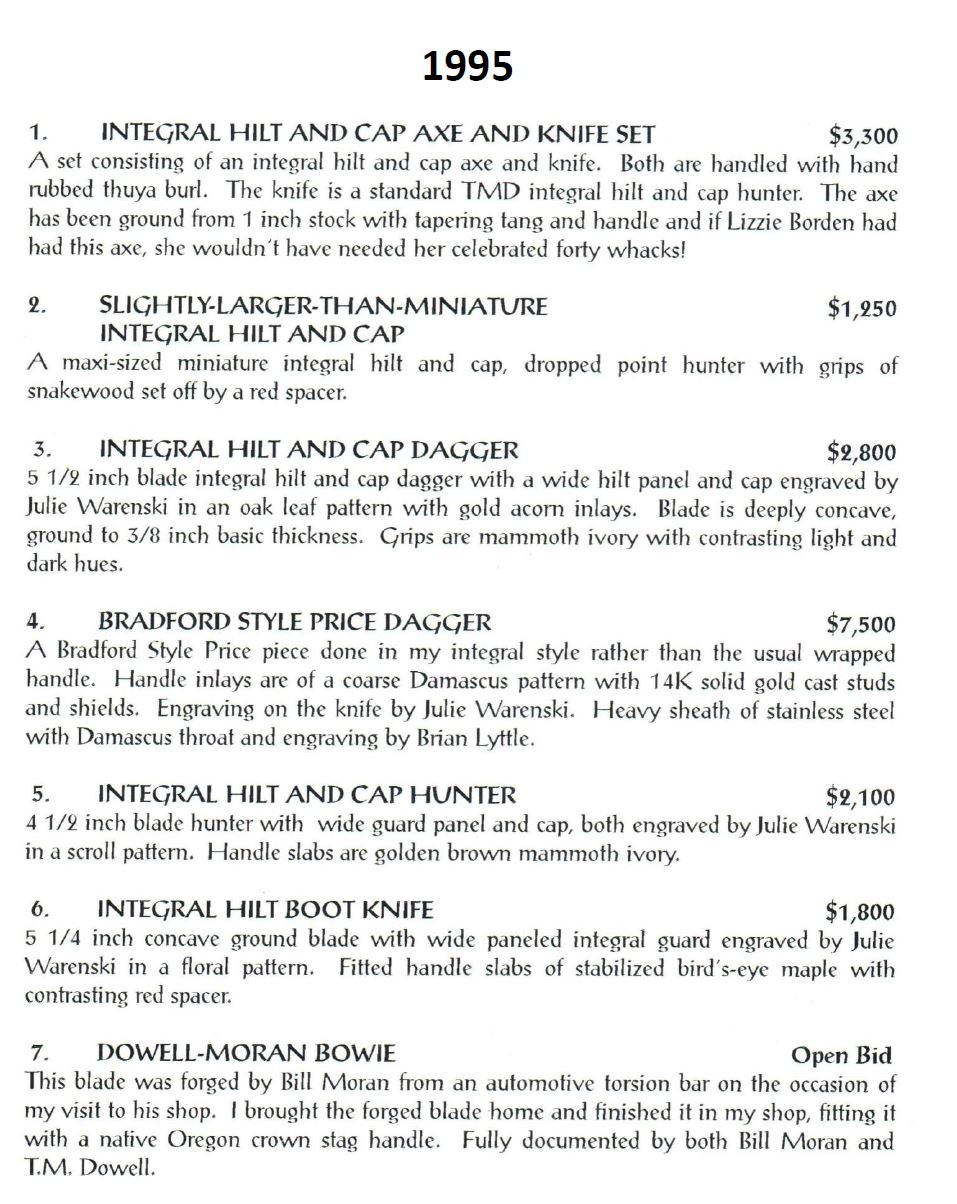

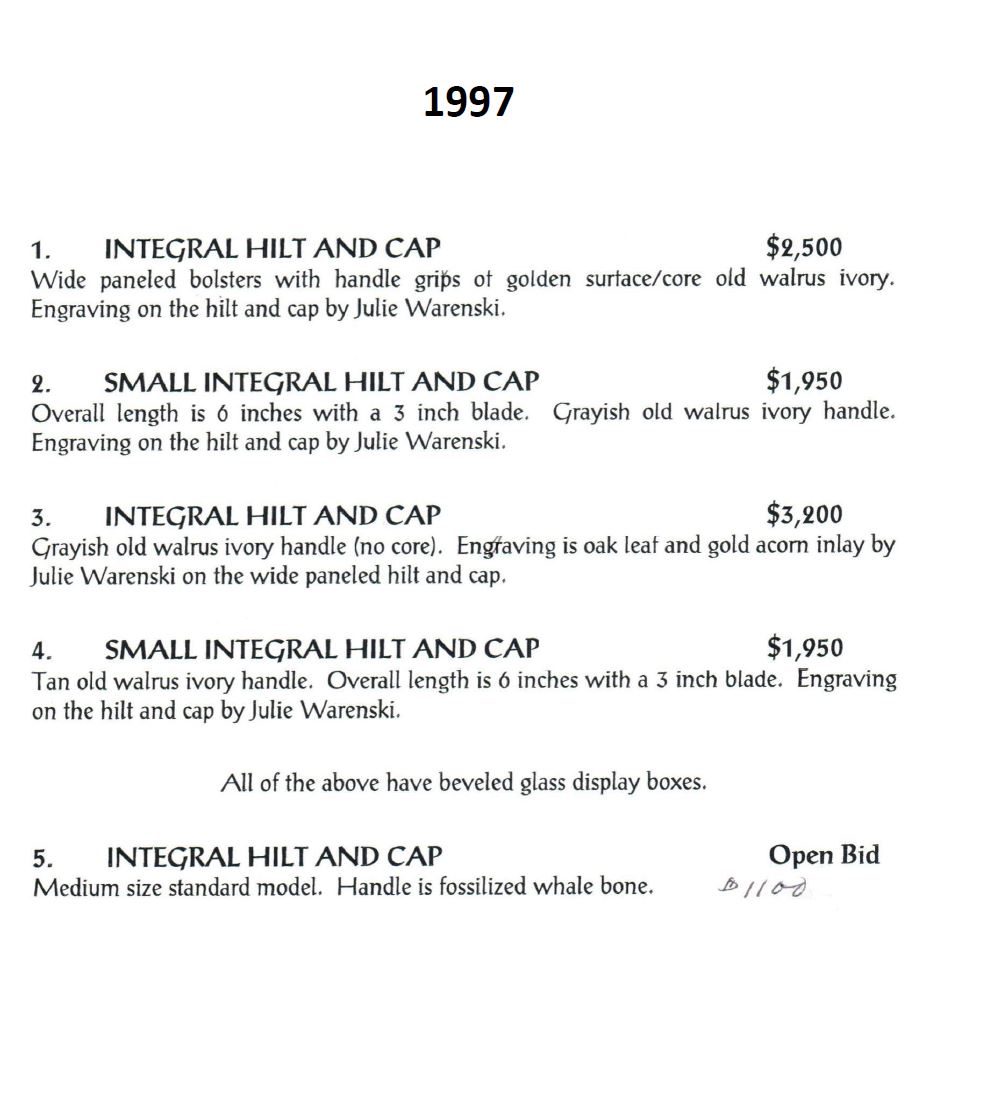

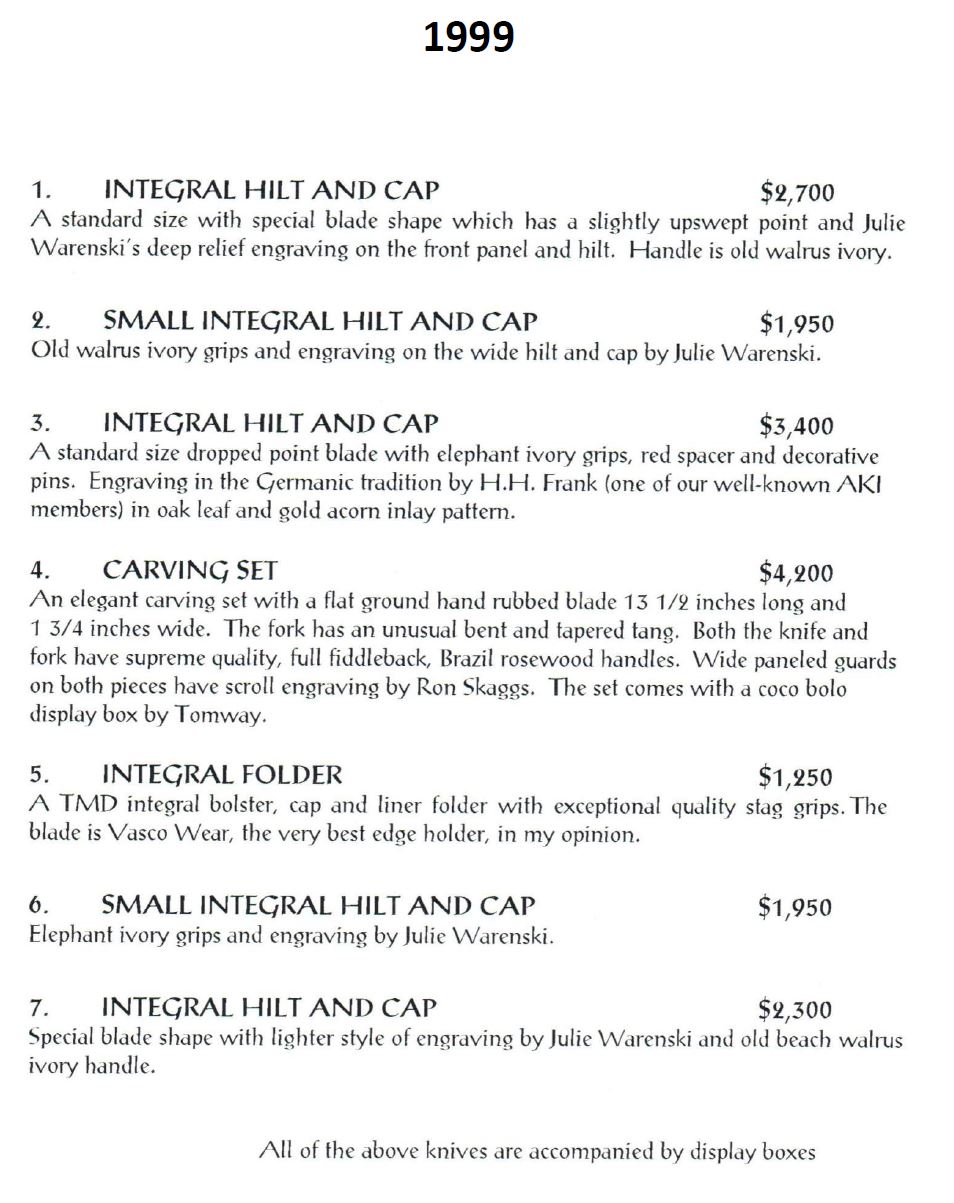

Lobred’s AKI proved to be a perfect venue for Ted, by which to display his most artistic creations; he, along with the rest of the Art Knifemakers of the world. TMD exhibited every year from 1983 to 1999, offering 33 Art Knives for sale to hundreds of AKI bidders. See the knife list TMD offered for each show below. You can also see pictures of many TMD’s AKI Knives in the Galleries section of this site.

In the early ‘80s Dowell purchased a power hammer in order to offer Damascus blades to a growing number of collectors who were asking him for Damascus knives. Early in his career, Dowell was not interested in doing any forging, as he preferred the ‘stock-removal’ method of blade creation. But the beautiful Damascus introduced by his good friend Bill Moran in the late ‘70s ultimately changed his mind. Moran encouraged Ted on multiple occasions to get involved in forging, by way of obtaining his ABS (American Bladesmith Society) certification, which Dowell ultimately did.

TMD forged-blade knives first appeared in the 1979 catalog, with the first mention of TMD Damascus knives appearing in the March ’86 Newsletter. There are a limited number of TMD forged-blade knives and forged-blade Damascus knives that were produced. Estimates are, roughly 40 TMD Standard forged-blade knives were sold. A TMD forged Damascus knife is even more rare, with roughly half that number thought to be in existence. It is important to differentiate Dowell-forged Damascus knives from TMD’s that were made from Damascus steel which Ted occasionally purchased from ABS forgers from time to time.

Dowell’s first three Damascus-forged knives are shown here. One can readily see the progression, from top to bottom, of the maker’s Damascus forging skills in these initial three knives, with each getting slightly more elaborate and ornate. These initial 3 knives were made in 1985, and Ted’s Damascus forging skills improved significantly over time. The pictures above are a sampling of some of his better forged Damascus knives.

Dowell’s first three Damascus-forged knives are shown here. One can readily see the progression, from top to bottom, of the maker’s Damascus forging skills in these initial three knives, with each getting slightly more elaborate and ornate. These initial 3 knives were made in 1985, and Ted’s Damascus forging skills improved significantly over time. The pictures above are a sampling of some of his better forged Damascus knives.

An interesting side story to the Dowell – Moran relationship: In 1984, Moran presented a gift to Betty Dowell at the AKI show in Reno, NV. A few years earlier, Dowell’s were visiting Moran’s at Bill’s Fredrick, MD, shop, where they got see a diverse sampling of Bill’s non-knife forging capabilities. Betty saw what she remembers as a ‘somewhat generic’ door-knocker and offered to pay Bill to make her something similar. Her expectations were low, and after two years passed, she had all but forgotten about the conversation. What was given to her in Reno however, was an incredibly ornate and intricate door ornament that can best be described as a work of art. A one-of-a-kind Moran piece if there ever was one! The piece is still in the Dowell family collection.

An interesting side story to the Dowell – Moran relationship: In 1984, Moran presented a gift to Betty Dowell at the AKI show in Reno, NV. A few years earlier, Dowell’s were visiting Moran’s at Bill’s Fredrick, MD, shop, where they got see a diverse sampling of Bill’s non-knife forging capabilities. Betty saw what she remembers as a ‘somewhat generic’ door-knocker and offered to pay Bill to make her something similar. Her expectations were low, and after two years passed, she had all but forgotten about the conversation. What was given to her in Reno however, was an incredibly ornate and intricate door ornament that can best be described as a work of art. A one-of-a-kind Moran piece if there ever was one! The piece is still in the Dowell family collection.

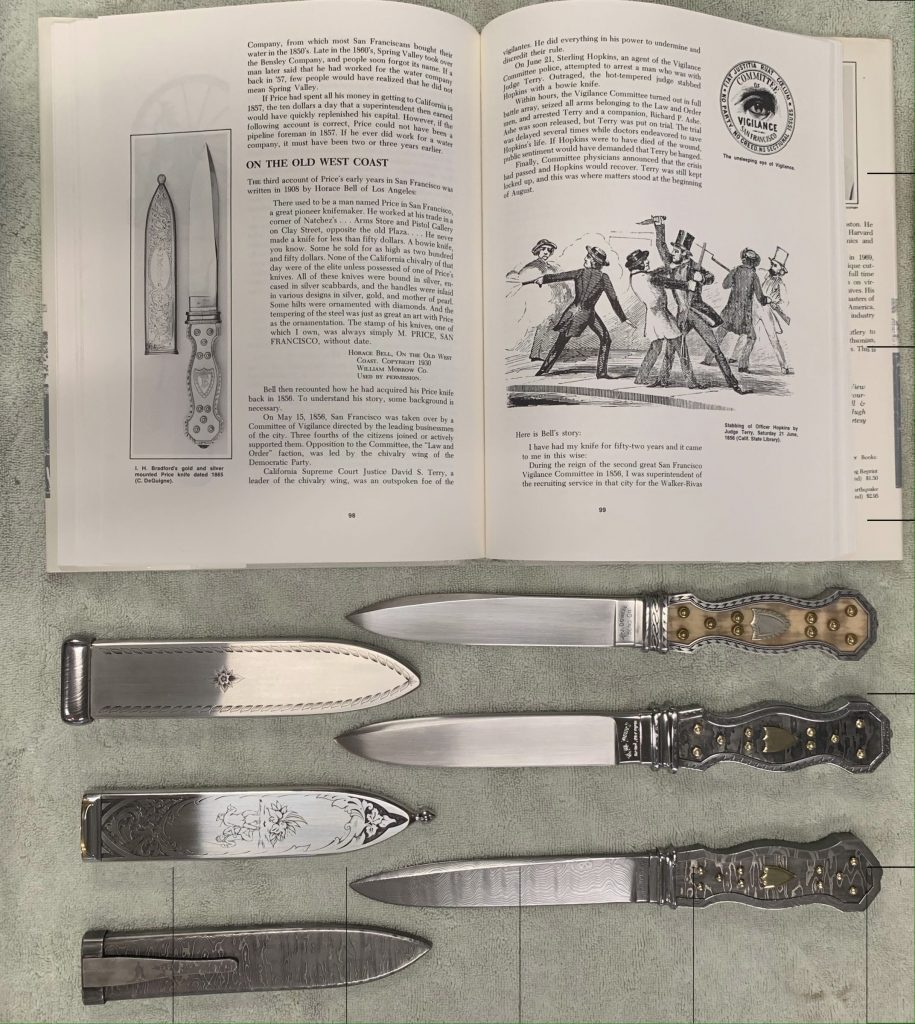

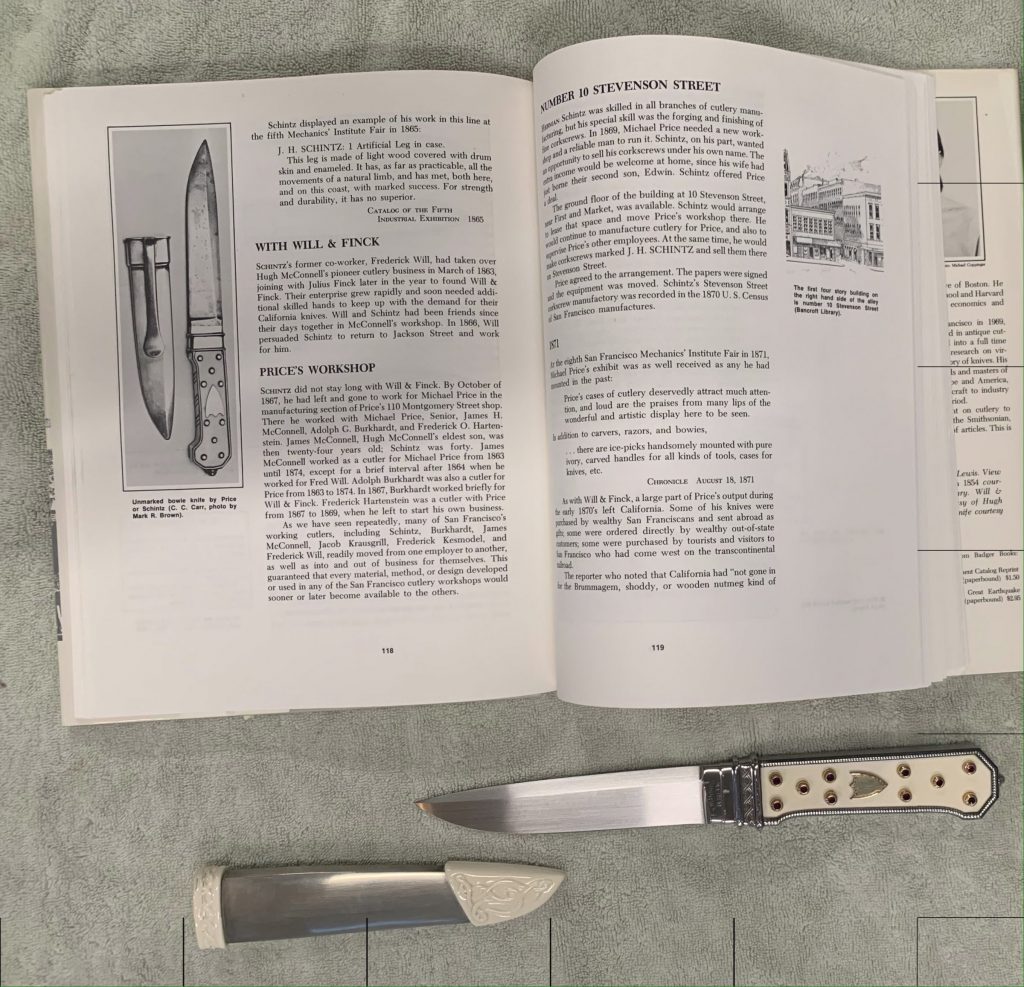

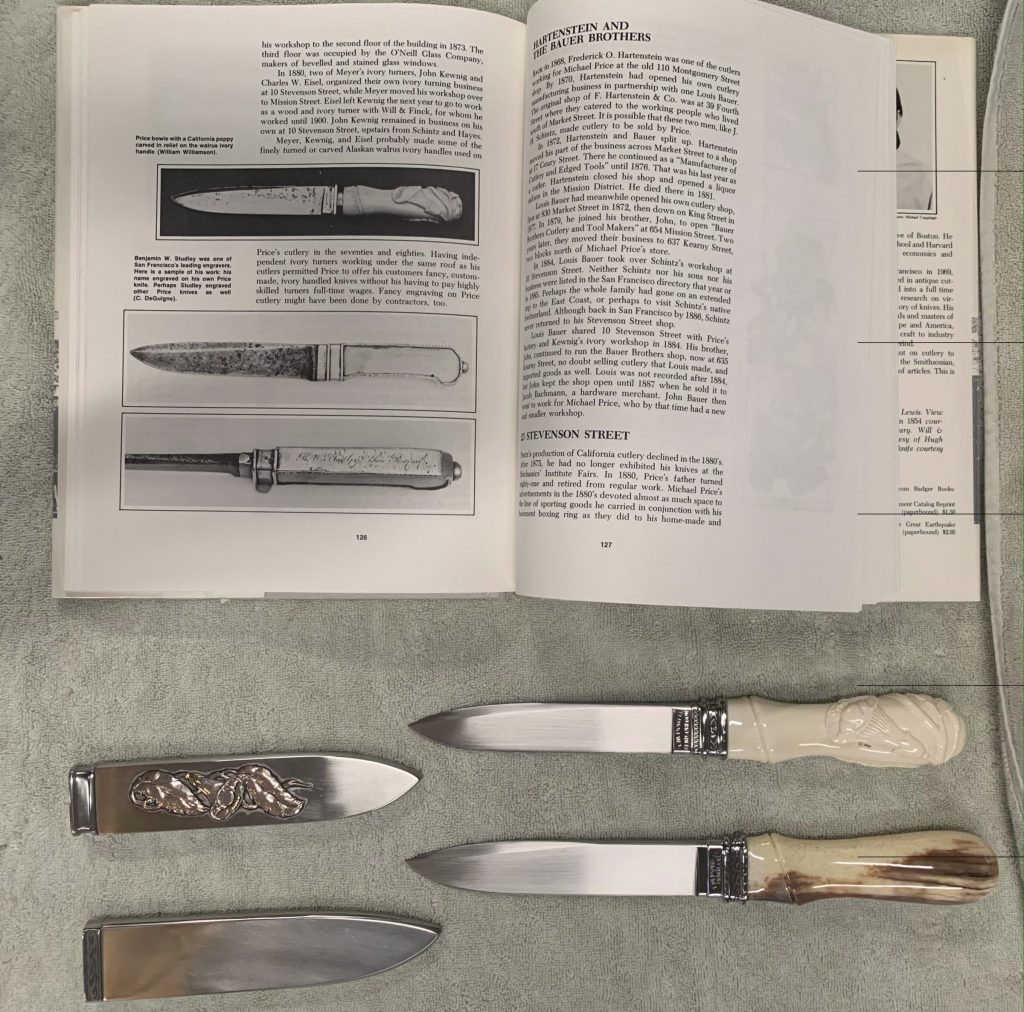

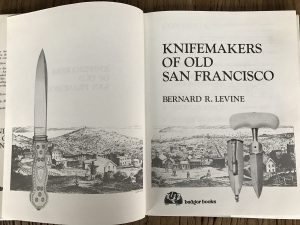

Ted did a significant amount of historical research before deciding what ‘path’ he wanted to take with his Art Knifes. Amongst the numerous books and articles he read and drew heavily upon, was Bernard Levine’s classic Knifemakers of Old San Francisco, where he found a handful of unique Michael Price Daggers from the 1860’s that particularly fascinated him.

Ted did a significant amount of historical research before deciding what ‘path’ he wanted to take with his Art Knifes. Amongst the numerous books and articles he read and drew heavily upon, was Bernard Levine’s classic Knifemakers of Old San Francisco, where he found a handful of unique Michael Price Daggers from the 1860’s that particularly fascinated him.

Over a 20-year span, from 1978 to 1998, Ted produced three different iterations of the Bradford Dagger, as well as three additional Price designs from that same book. This series ultimately grew into a set of eight fully Integral TMD Michael Price daggers, each with its own decorative sheath; and is considered by Lobred to be “the most complete set of Period Art Knives ever created.”

Phil Lobred initially purchased most of this series and held them for years. But in early 2016, just months before his passing, he agreed to sell them all to an undisclosed collector, where they, and all but one of the remaining daggers, have been aggregated, with the intent to preserve them in perpetuity, as a one-of-a-kind set.

As part of Ted’s fascination with California knifemakers in the 1800’s, he became intimately familiar with the ‘look’ of many of the famous pieces that were thoroughly documented in Bernard Levine’s book.

As part of Ted’s fascination with California knifemakers in the 1800’s, he became intimately familiar with the ‘look’ of many of the famous pieces that were thoroughly documented in Bernard Levine’s book.

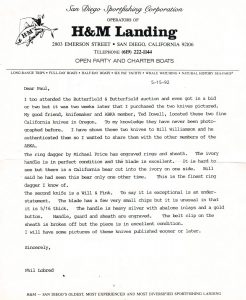

In early 1993, Dowell had a knife supply rep stop by as he and Betty were getting ready to leave for a tradeshow. They had both Ted’s Michael Price integral ring dagger and a Will and Fink bowie replica sitting on the kitchen table. The rep casually commented, “I’ve got a buddy who has two knives just like that”. Ted, trying to hold back his shock at the statement replied, “Really? – tell me more”. The rep said his friend had received the knives decades earlier and held onto them just because he ‘liked the look of them’.

Dowell then proceeded to set up a personal viewing of the knives, during which he was able to verify they were originals. He told the owner that he thought they might be valuable and requested his permission to have a friend contact him directly to provide an estimate of their worth.

That friend was Phil Lobred. Dowell believed there was nobody more worthy or deserving of having a shot at owning such rare collectibles, and Lobred jumped at the opportunity. The two parties met, a deal was done, and Phil became the proud owner of what turned out to be two of the most pristine and valuable knives of the 1850’s era, as evidenced by this correspondence between Phil and an ABKA member. Lobred’s debt of gratitude and appreciation for Ted grew significantly from this event.

That friend was Phil Lobred. Dowell believed there was nobody more worthy or deserving of having a shot at owning such rare collectibles, and Lobred jumped at the opportunity. The two parties met, a deal was done, and Phil became the proud owner of what turned out to be two of the most pristine and valuable knives of the 1850’s era, as evidenced by this correspondence between Phil and an ABKA member. Lobred’s debt of gratitude and appreciation for Ted grew significantly from this event.

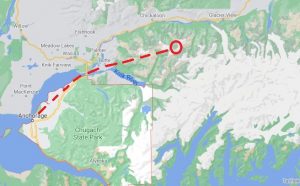

Phil & Judy Lobred and Ted & Betty Dowell became friends very early in Ted’s knifemaking career. Phil was a collector of many makers in the late 60’s, while living in Alaska. He purchased and used several TMD hunting knives during this time, and in late 1975 took Ted on a memorable week-long moose hunting trip into the remote Alaskan wilderness.

Phil & Judy Lobred and Ted & Betty Dowell became friends very early in Ted’s knifemaking career. Phil was a collector of many makers in the late 60’s, while living in Alaska. He purchased and used several TMD hunting knives during this time, and in late 1975 took Ted on a memorable week-long moose hunting trip into the remote Alaskan wilderness.

During a subsequent visit to Bend, Phil spent many days in the shop with Ted and youngest son Jeff, who had taken over not only sheath making responsibilities but also the majority of the ‘stock removal’ work associated with the Integral knives that Ted was focused heavily on. The time the three spent together not only deepened the connection between Ted and Phil but also laid the foundation for a life-long relationship between Phil and Jeff, where Phil mentored the younger Dowell on his growing interests in knife collecting.

During a subsequent visit to Bend, Phil spent many days in the shop with Ted and youngest son Jeff, who had taken over not only sheath making responsibilities but also the majority of the ‘stock removal’ work associated with the Integral knives that Ted was focused heavily on. The time the three spent together not only deepened the connection between Ted and Phil but also laid the foundation for a life-long relationship between Phil and Jeff, where Phil mentored the younger Dowell on his growing interests in knife collecting.

Phil was not only one of TMD’s biggest collectors but also rightfully credited with giving Ted the multiple pushes he needed to add Art Knives to his repertoire in the ‘70s, the ‘80s, and the ‘90s.

Phil was not only one of TMD’s biggest collectors but also rightfully credited with giving Ted the multiple pushes he needed to add Art Knives to his repertoire in the ‘70s, the ‘80s, and the ‘90s.

In 2007, son Jeff decided it was time to get Phil and Ted back together for one final hunting trip. This one, to Ted’s ‘stomping grounds’ in Central Oregon. Betty and Jeff’s wife Pat joined in for a magical weekend of whiskey-sipping and campfire reminiscing.

By 2008, Ted’s quality of life and his workmanship were deteriorating due to the onslaught of Dementia, and Betty was careful to see to it that very few pieces of his work after this time ever made it to the marketplace. She felt, correctly so, they were just not representative of the TMD brand, and they were not something she wanted out there to tarnish his legacy. That said, Ted was still in the shop every day, working on knives, and it was during this time that he produced what came to be known as ‘The Last…’ series; a small collection of his final efforts to produce one last piece of each of his signature knives. The last Featherweight. The last Integral Hilt. The last Integral Hilt and Cap.

By 2008, Ted’s quality of life and his workmanship were deteriorating due to the onslaught of Dementia, and Betty was careful to see to it that very few pieces of his work after this time ever made it to the marketplace. She felt, correctly so, they were just not representative of the TMD brand, and they were not something she wanted out there to tarnish his legacy. That said, Ted was still in the shop every day, working on knives, and it was during this time that he produced what came to be known as ‘The Last…’ series; a small collection of his final efforts to produce one last piece of each of his signature knives. The last Featherweight. The last Integral Hilt. The last Integral Hilt and Cap.

These pieces came about, not because he was still capable of producing them from scratch; rather, because he was able to draw from an inventory of already ground and heat-treated stand-alone blades; having been created years before, but never completed. These ‘blanks’ provided perfect fodder from which to ‘continue his craft’ – unaware that he no longer possessed the required skills to do so.

These pieces came about, not because he was still capable of producing them from scratch; rather, because he was able to draw from an inventory of already ground and heat-treated stand-alone blades; having been created years before, but never completed. These ‘blanks’ provided perfect fodder from which to ‘continue his craft’ – unaware that he no longer possessed the required skills to do so.

These knives, when completed by Ted, were not his best efforts; particularly when measured against his earlier work. Yet by now, he was not always able to discern this, and he kept producing them – because that’s what he’d done for decades; why would it be any different now?

Once perfect grind lines on blades were destroyed by hands that could no longer hold steady against a grinding wheel. Where once the hilts and handle slabs artfully blended, they now had larger than normal gaps. In the case of his final integral hilt knife, the entire piece was unknowingly re-ground upside down; such that the hilt sloped forward instead of its classic backward angle. Additionally, TMD branding escutcheons were placed noticeably off-center in handles. Grips were even attached with entire pin sets missing. All this, from a once-great craftsman and artist, who was unable to recognize the degraded quality of his work. But Betty, knowing otherwise, quietly tucked them away, and Ted was none the wiser.

It wasn’t until years later, after Ted had passed away, that the family came across these knives again and realized the symbolic significance of them – despite their inferior workmanship. A handful of them were subsequently combined with their ‘twins’ from the beginning of Ted’s career, as well as with representative ‘best-of-class’ knives of the same model and placed into thematic sets. They represent the works from the full spectrum of the maker’s career: from early, to the best-of-class, to the declining end-of-life phase of both the knives, as well as the man who created them. Pictures of some of these sets can be seen here: First and Last Featherweights and First and Last Integrals, etc.

The Closing of the Shop: Continuing injuries to Ted that increased in both frequency and severity led to the difficult decision to lock-down the shop and create a makeshift work area with a vise and some basic tools on an attached back porch of the house. This helped to ease the burden on Betty, as it gave Ted a place to go and ‘work’, which he did pretty much every day for a few more years.

The Closing of the Shop: Continuing injuries to Ted that increased in both frequency and severity led to the difficult decision to lock-down the shop and create a makeshift work area with a vise and some basic tools on an attached back porch of the house. This helped to ease the burden on Betty, as it gave Ted a place to go and ‘work’, which he did pretty much every day for a few more years.

Betty’s Heart Surgery: Caring for Ted 18 hours a day for almost a decade took its toll on Betty. She eventually required open-heart surgery in 2012. During her time in the hospital, family and friends came together to help care for Betty (in the hospital) and Ted (at home). It was very challenging. Betty had an extended recovery, and those caring for Ted came to quickly realize how much work it was to wake him, bathe him, feed him, and keep a watchful eye, whenever he was on the back porch.

Betty’s Heart Surgery: Caring for Ted 18 hours a day for almost a decade took its toll on Betty. She eventually required open-heart surgery in 2012. During her time in the hospital, family and friends came together to help care for Betty (in the hospital) and Ted (at home). It was very challenging. Betty had an extended recovery, and those caring for Ted came to quickly realize how much work it was to wake him, bathe him, feed him, and keep a watchful eye, whenever he was on the back porch.

The Dreaded Nursing Home Decision: It became obvious to everyone that Ted was going to be far more work to care for than Betty was ever going to be able to handle again. When she did return home, Ted was not there. He had been put in a memory care center the week before. He lasted about eight weeks. On the occasional moments when he was lucid, and he knew where he was, he hated it. He was visited by family and friends daily, but the visits were painful, as Ted’s health was steadily declining. And for the most part, he did not recognize any of his visitors.

The Dreaded Nursing Home Decision: It became obvious to everyone that Ted was going to be far more work to care for than Betty was ever going to be able to handle again. When she did return home, Ted was not there. He had been put in a memory care center the week before. He lasted about eight weeks. On the occasional moments when he was lucid, and he knew where he was, he hated it. He was visited by family and friends daily, but the visits were painful, as Ted’s health was steadily declining. And for the most part, he did not recognize any of his visitors.

The Passing(s): Ted Dowell passed away the evening of October 5, 2012, under hospice care, just two days after his and Betty’s 59th wedding anniversary. Though deeply saddened, for the family, it was a blessing. TMD’s final decade had been anything but kind, and in the end, Dementia proved to be a ruthless and relentless foe.

The Passing(s): Ted Dowell passed away the evening of October 5, 2012, under hospice care, just two days after his and Betty’s 59th wedding anniversary. Though deeply saddened, for the family, it was a blessing. TMD’s final decade had been anything but kind, and in the end, Dementia proved to be a ruthless and relentless foe.

Jeff sadly recalls the phone call he made to Phil Lobred to inform him of Ted’s passing,  as well as the equally difficult personal visit to Betty, to tell her of the loss of Phil four years later.

as well as the equally difficult personal visit to Betty, to tell her of the loss of Phil four years later.

The Obituary: Ted’s Obituary can be found below.

Betty Dowell: Betty still lives in the original Bend, OR, house, and at nearly 90, is in pretty good health, with a mind as sharp as ever. She enjoys her days talking and visiting with family and friends and has on-going conversations with multiple surviving members of the knifemaking community that she and Ted were such an integral part of for so many years.

If you know Betty, and want to reach out via email, you can click here.